In Holland during World War II and the decade leading up to

it a Christian family sheltered Jews from Nazi arrest and in

consequence were themselves arrested.

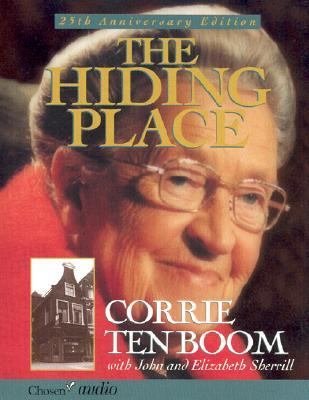

The Hiding Place by the Dutch lady Corrie ten

Boom, with co-writers John and Elizabeth Sherril, tells the story of

courage in the face of evil – or rather it shows the power of God’s light to

shine in the darkness. In my view the horrors of Germany in that period arose

from a kind of supernatural belief in the superiority of the Teutonic race and

the supernatural destiny of the German nation. Nationalism had already gained a

hold in the decades leading up to World War I and this nationalism had arisen

to fill a spiritual vacuum created by attacks on the Christian faith and its institutions by German writers and philosophers

such as Hegel, Marx and Nietzsche.

The Hiding Place by the Dutch lady Corrie ten

Boom, with co-writers John and Elizabeth Sherril, tells the story of

courage in the face of evil – or rather it shows the power of God’s light to

shine in the darkness. In my view the horrors of Germany in that period arose

from a kind of supernatural belief in the superiority of the Teutonic race and

the supernatural destiny of the German nation. Nationalism had already gained a

hold in the decades leading up to World War I and this nationalism had arisen

to fill a spiritual vacuum created by attacks on the Christian faith and its institutions by German writers and philosophers

such as Hegel, Marx and Nietzsche.

Apart from the general cautionary lesson on the horrific

consequences of aggressive atheism when malignant forces rush to fill the

spiritual vacuum, a number of passages had a special impact.

After World War II finished a former prison camp guard asks

Corrie ten Bloom to forgive him, as Christ commanded. She cannot bring herself

to do this. He offers her his hand.

‘And so again I

breathed a silent prayer. Jesus, I cannot forgive him. Give me your

forgiveness...as I took his hand the most incredible thing happened. From my

shoulder along my arm and through my hand a current seemed to pass from me to

him while into my heart a current seemed to pass from Him while my

heart sprang a love for this stranger that almost overwhelmed me.

‘And so I discovered that it is not on our forgiveness any

more than our goodness that the world’s healing hinges but on His. When He

tells us to love our enemies, he gives along with the command, the love

itself.’

Earlier in the book she and her sister were holding an

underground multi-denominational service in Barrack 28 which, incredibly,

no-one stopped. 'Roman Catholics, Lutherans and Eastern Orthodox took part

together. They were little previews of heaven, these evenings below the light

bulb. I would think of Haarlem (the town in Holland where her family had sheltered

Jews), each substantial church set behind its wrought-iron fence and its

barrier of doctrine. And I would know again that in darkness God’s truth shines

most clear.’

A few pages before she had obtained a Bible which she hid in

a small bag. ‘Sometimes I would slip the Bible from its little sack with hands

that shook, so mysterious had it become to me. It was new, it had just been

written. I marvelled sometimes that the ink was dry. I had believed the Bible

always, but reading it now had nothing to do with belief. It was simply a

description of the way things were – of hell and heaven, of how men act and how

God acts. I had read a thousand times the story of Jesus’ arrest – how soldiers

slapped Him, laughed at Him, flogged Him. Now such happenings had faces and

voices.’

In the years before the war there is a chilling observation

by her brother Willem, who was studying at a German university. Only a

century before godlessness was corroding the souls of the German intelligentsia

and this, I believe, was the result:

‘Oftentimes, indeed, I wished that Willem did not see quite

so well, for much that he saw was frightening. A full ten years ago, back in

1927, Willem had written in his doctoral thesis, done in Germany, that a

terrible evil was taking root in that land. Right at the university, he said,

seeds were being planted of contempt for human life such as the world had never

seen. The few who had read his paper had laughed.’

A spiritual vacuum had been created by German philosophers

such as Marx, Hegel and Nietzsche. When belief in God is eroded history shows that

people believe in anything.

Occultism and the concept of the superman started with Nietzsche(1844-1900) who preached against the teachings of Christ. Before being pronounced insane he managed to

plant into the mind of many an intellectual the belief that all depended on you,

not God, and that if you did not dominate others you deserved to be dominated .

The weak and poor in spirit were to be despised

and exploited. Nationalism, arising to replace Christianity, led the unfortunate German people to seek world

domination in World War I (1914-1918) as well as World War II (1939-1945).

The growing darkness did not manifest itself in elections

even as late as 1928, when the Nazi Party received only 2.8% of

the popular vote, having only 12 seats out of 491 in the Reichstag. In 1933 the

Nazi vote had risen to 43.9%. Jews, the disabled, gypsies, old people and communists were

subject to persecution, both officially and through individuals who had absorbed Nazi doctrine and believed in the power of the clenched fist.

Could anyone have forecast this? Or the horrific effects of

Stalinism in Russia and Maoism in China? Hundreds of millions of lives lost throughout the 20th century and

many more ruined by eclipsing the Creator with human pride, albeit with good intentions in the case of Communism. Could something similar happen again even in a

secular Parliamentary democracy, as Germany was at the time the Nazi Party rose to power? I invite you to reflect on this.